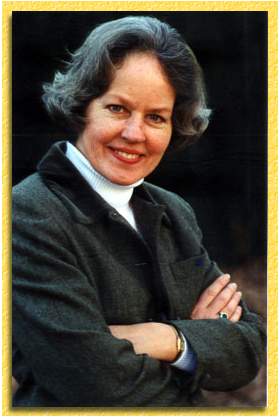

Profile – Keeping Up With Anita Jones

From Texas techie to Defense Department dignitary, the life and times of an engineering powerhouse.

Anita Jones is one of those people you just have to ask: “What’s your secret?” A powerhouse of science and technology with an impossibly long list of credentials, Jones works at the highest echelons in a field long dominated by men-simultaneously playing key roles in academia, industry, and government – and she makes it all look easy. That’s because, she explains, she followed her father’s advice: “Choose something to do in life that you love more than fishing.”

What Jones loves more than anything is the idea of creating something out of nothing. That passion propelled her to become one of the first female Ph.D.s in computer science, and later to become the federal director of defense research and engineering, the highest Defense Department job ever held by a woman.

These days, she divides her time between teaching computer science at the University of Virginia, holding board positions with computing industry corporations, and serving on a dizzying array of top advisory boards for national security and high technology matters.

Through it all, the born-and-bred Texan keeps everything in a characteristically understated perspective. “I see my life as a series of creeks running alongside one another,” Jones explains. “There’s my national security work, my teaching life, my industry life, and my private time with my husband and in the garden. I just hop back and forth between the creeks.”

“The best that life can give you is the opportunity to try to do something that is worthwhile.”

Early Encouragement, Early Success

When Jones was growing up in Houston in the 1950s, a young woman was expected to go to college mainly to round out her education before marrying and becoming a housewife. But Jones’ father, a petroleum engineer, always encouraged her to devote herself to something-what that thing was didn’t matter so much, the idea was to do it. He taught her to play chess, helped her work on geometry problems, and on weekends took her and her younger brother fishing for catfish, red snapper, and trout on Galveston Bay. Jones’ mother, who had trained as a ballerina and danced in several Hollywood films, taught her daughter a love of painting.

But when Anita graduated as valedictorian of her high school class in 1960, it was the lure of the burgeoning computer science revolution that most captivated her. “It was a whole new area then, and it was going to change the world,” Jones recalls. “You would be able to build things that would do a piece of what human beings do.” The field was so new, in fact, that Rice University did not yet have a computer science department; Jones majored in mathematics.

With bachelor’s degree in hand, Jones did not get married, nor did she rush into a career. Remembering the advice to have fun, Jones decided to round out her education with a master’s in English literature from the University of Texas. As graduate school drew to a close, Jones thought “long and hard” about what fields would be most important in shaping the world to come. She considered biology and psychology, but in the end could not resist computer science. Just before graduation, she quickly took a short class in FORTRAN programming, one of the only computing courses offered at UT, in order to win a job with IBM. A few years there convinced Jones that computing was for her, but she longed to be more in control of what she did and decided to head back to graduate school again-first at MIT, then at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh-for a computer science Ph.D.

It was at Carnegie-Mellon that Jones first got the sense that she was parting company with traditionally raised Texan women and setting off on an unorthodox adventure. Jones’ collegiality and curiosity soon helped her form close ties with fellow students, who all felt like early pioneers at a special time in history. Soon, an informal gang known as the “brownie plate group” emerged; every day at lunch, these students would turn over the thick brown pieces of cardboard that their brownies were served on in order to jot down notes from their brainstorming sessions on a problem from class or some especially challenging part of one member’s thesis. (Jones’ thesis was, precociously, on the importance of security for computer networks.)

When not in the cafeteria, Jones networked with students at CMU and 50 other universities through ARPANET, the first incarnation of the Internet. The computer science community was so tight-knit that when Jones earned her Ph.D., the logical thing to do was to continue research within the academic world, so Jones began teaching computer science at Carnegie-Mellon.

A Formidable Team

For four years she commuted back and forth between Washington, D.C., and Charlottesville, sometimes making the five-hour round trip drive in one day and other times staying at a one-bedroom apartment near the Pentagon. Just as her post was ending, her husband was elected president of the National Academy of Engineering, also in D.C. Jones says the commuting life is “just barely tolerable” and is made easier by the fact that Wulf is also a workaholic. “It helps to have a spouse who is supportive of a demanding schedule,” she emphasizes. Even more valuable, she says, is Wulf’s ability to discuss work matters with her and give her valuable insights. “I’ve learned more from Bill than from anyone else in my life,” she says.

“I always thought that if you shoot for the moon and fail, you still land among the stars.”

Help From Her Friends

Jones emphasizes that she wouldn’t be where she is today without the help of several colleagues and mentors all along the way. “Every woman encounters some obstacles,” she says, “But my experience was never one of trying to break through glass ceilings. Rather, doors were opened for me everywhere I went. And when I walked through one, two more would open.”

That’s probably because she has always earned tremendous respect among her peers. John Seely Brown, the chief scientist for Xerox Corporation and a longtime associate of Jones, says that she has “the amazing talent of knowing how to support radical efforts on the one hand and knowing what it takes to make them pay off in the global economy on the other.”

Another longtime colleague, Vint Cerf, a senior vice president at MCI WorldCom, adds that Jones is especially gifted at consensus building, and has been a great role model for other women seeking to make their mark in the field.

Most of all, Jones is known as a down-to-earth, kind person. “Every Monday during the summer, my desk is full of gorgeous, colorful flowers,” says Peggy Reed, Jones’ assistant at UVA. (The flowers are from Jones’ extensive gardens. Sometimes they are accompanied by vegetables, grown by Wulf.) “I don’t know too many bosses who bring their employees gifts every week.”

Eager to Learn, Quick to Fit In

Jones attributes most of her success to her willingness to branch out in all directions and to continually learn new things. When she was a young professor at CMU, an associate asked her to be part of the U.S. Air Force Scientific Advisory Board. She knew nothing about the Air Force, but accepted anyway. “I was 20 years younger than everyone else, and by learning from some of the brightest minds in the country, my understanding of technology issues expanded far beyond what I was even capable of comprehending before.” Jones never saw such moves as risky or threatening. “It may sound trite, but I always thought that if you shoot for the moon and fail, you still land among the stars,” she says.

Her venture on the Air Force Advisory Board would not only land her on the board of directors of several other organizations, but would ultimately lead her to be appointed by Clinton as the top-ranked woman in the Defense Department, just two positions below the Secretary of Defense. “The first week I took the job I read a graduate text on radar,” Jones remembers. “And every week after that I learned something else that was new.”

Today’s Challenges

Jones says that her DoD experience has led her to broaden the perspective she passes on to her students. Now back at UVA, she emphasizes the myriad ways in which science influences every aspect of life, from global warming, to improvements in treating health problems, to the impact of the Internet on commerce. She has just launched a course in science technology policy, in which students must put together a good explanation of the scientific basis for a public policy proposal. She also reminds them that technology is only valuable when it benefits people. One thing she is “just passionate about” these days is the challenge of building “survivable systems” with information technology embedded in them. The infrastructure of a company, emergency government services, telephone systems, and electricity power grids are all too fragile, she warns, vulnerable to natural hazards, errors in the system, and enemies.

Even though she is busy teaching, Jones still travels every week, commuting to D.C. to consult at the Pentagon and throughout the country to meet with task forces that tackle questions like “What part can the DoD play against narcotic traffickers?” and “How can we use science to protect peacekeeping forces?” She says she doesn’t have any desire to slow down her pace, because, “The best that life can give you is the opportunity to try to do something that is worthwhile.” In her book, that’s far better than fishing.

Joannie M. Schrof is a senior editor at U.S. News & World Report.

Category: Features